Recently I was looking at a colleagues’ hot water system and pointed out that his solar thermal system had no pressure in it. He assured me that the local installer had said it didn’t need recharging and that the system was working properly. So, what is the point of having pressure in the system? Well, almost all solar thermal systems are pressurised with anti-freeze based heat transfer fluid and are sealed and pressurised. We’re all used to having to top up the pressure on our boilers from time to time and our boilers usually flash up an error code and stop working if the pressure drops below a certain point. To be fair, some of the latest solar thermal system controllers do this too, but the vast majority will carry on working with virtually no pressure in them.

The main reason that solar thermal systems should be kept pressurised is to raise the boiling point of the heat transfer fluid. Even a basic flat plate solar collector can generate very high temperatures which turn the fluid into high pressure vapour which is forced around the system and into the expansion vessel. This superheated vapour can eventually lead to damage to the system such as perished seals or a leaking expansion vessel diaphragm. Furthermore, each cycle of vapourisation and recondensation degrades the heat transfer fluid slightly. Eventually the heat transfer fluid gathers acidity and the system starts to eat itself from the inside.

Now a well designed solar thermal system will have enough of a “load” to avoid frequent vaporisation of the fluid. In other words, the hot water storage cylinder has to be big enough to ensure there is a volume of water which still needs heating. This is achieved by having a tall thin cylinder where the coldest is at the bottom in the so called dedicated solar zone. On summer days when you’re not using a lot of hot water, your whole cylinder will quickly reach its maximum temperature (usually 60°C to avoid scalding) and then there’s no “load” for the solar thermal system. The solar thermal controller turns off the circulation pump and the fluid in the solar collector quickly reaches its boiling point. This is called stagnation. To protect the system from damage, the solar thermal controller doesn’t allow the pump to switch back on again until the collector has cooled sufficiently. This can often be after sunset so if you do start using hot water in the late afternoon, the solar thermal system can sit there doing nothing until the following day and you miss out on some of the free solar hot water.

The whole point of having your system pressurised is that it stops the system going into stagnation as often so you get a better energy yield and your system lasts longer.

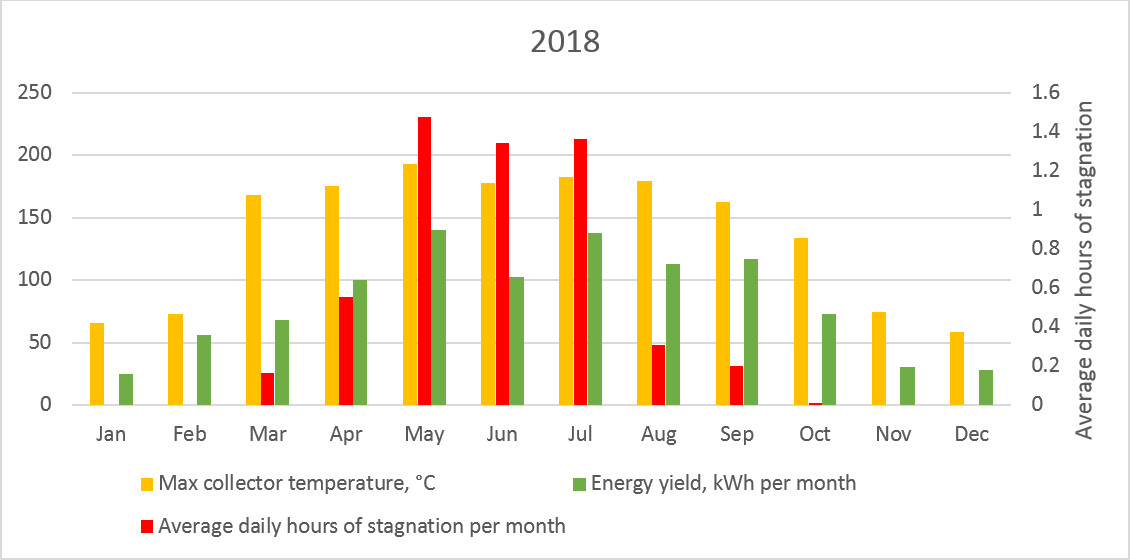

With all of these thoughts still fresh in my mind, I went straight home and had a look at my own solar thermal system. The pressure gauge was also at zero! My system has a datalogger on it so I analysed the historical data and I can see now that sometime in 2017 my system pressure must have dropped because the system started stagnating on a regular basis throughout the summer.

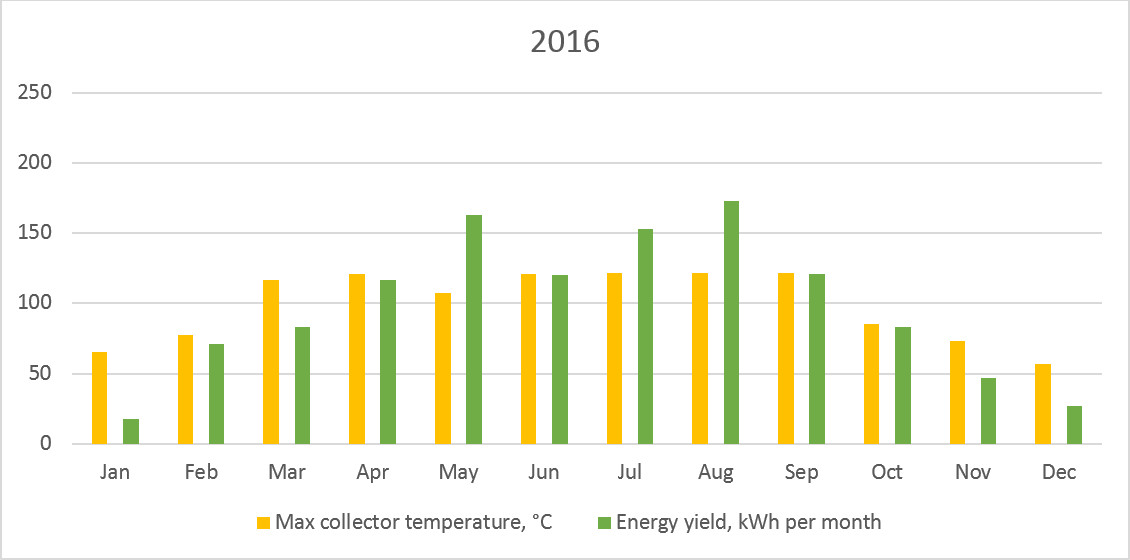

The 2016 chart shows that the solar collector never went above 120 degrees C so the system never went into stagnation. The energy yield measured by my system heater meter in 2016 was 1176kWh.

Compare this with 2018 and the energy yield had dropped by 15% to 992kWh. The red bars shows the average number of hours each month that the system had gone into stagnation. Most of the energy yield loss would be because the system quickly stagnated and was then “locked out” for several hours before cloud cover or darkness allowed the collector to cool again.

So I too need my system recharged. Unfortunately, topping up the pressure on a solar thermal system is a little more involved than it is on a boiler. You have to be able to add fluid without introducing air so it’s usually something best left to an installer who will normally hook the system up to a powerful commissioning pump. Whilst they’re at it they should check the pH of the fluid with litmus paper and that the fluid still has adequate anti-freeze properties with a refractometer. That’s a job for me for the weekend!

Update

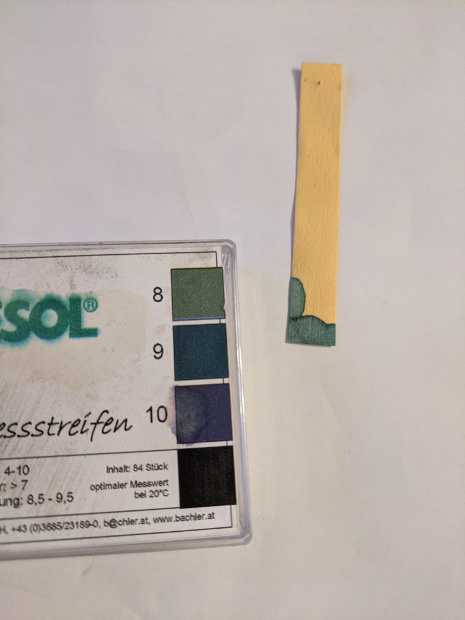

It was raining on Sunday so I got busy and serviced the whole system. I started by inspecting the pipework and tightened up a couple of compression fittings where there was evidence of glycol weeping. Next, I checked the heat transfer fluid for pH and refractive index. The pH was around 8.5 which is OK.

The refractometer I used was calibrated for propylene glycol and showed that freezing point of the fluid is -25 degrees C which is more than adequate for the Newcastle area. I released what was left of the pressure in the system and then checked the pre-charge in the expansion vessel.

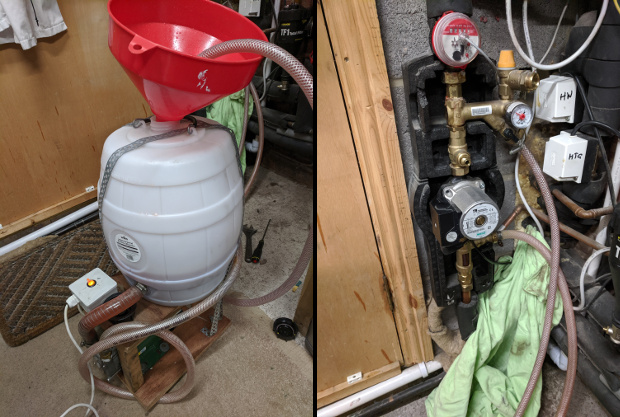

This was at 1.5 bar which was OK for my system. I then rigged up a commissioning pump using some old home-brew kit and a shower pump.

The pump-station on my solar system comes with a couple of commissioning valves which allow you to push fluid right through the system and circulate it round to eliminate any pockets of air. With my home made setup this only took a few seconds and I was then able to close the return valve and let the pressure build up to 2 bar.

After resetting all the valves to their original position and removing my temporary pump, I switched the solar thermal circulation pump on manually to check the flow rate and make sure it was all running silently. Any noise in the system at this point would indicate that there is still air in the system and this can cause damage to the pump through cavitation so it’s quite important to make sure it all runs silently. With the system hydraulics in great shape, the only thing that remains to be done is to give the collector a clean. I might wait until it’s not raining to do that.

Alex Savidis is a renewable energy technical specialist at Decerna. He’s currently working on delivering energy efficiency advice to local businesses through the ERDF funded BEST project www.best-ne.co.uk as well as delivering consultancy on energy storage and renewables to a variety of private and public sector clients.